Matthias Schulze, 07.10.2024

The aim of this multipart blog series is to take a closer look at the various definitions one can find and dissect what types of actions the term “active defense” describes and how it contributes to security. The confusion with it stems from multiple reasons.

1) it is a political term, a framing to be more precise, to frame certain cyber-activity under a palatable term. Active sounds nice. There is action, activity and not just pure reactivity. For some it means not just taking punches but actually doing something, getting the initiative back. These are all positive connotations. 2) the term has been used in industry as a marketing term for similar reasons: It just sounds better than plain old information security or cyber-security, and thus all kinds of different products can be sold under the term. 3) The terminology lies at the intersection of various epistemic communities (communities of practitioners that have a different background and interpretation of the term) such as military, technical cybersecurity, politics, law, and intelligence. That means for a military General, active defense means something entirely different compared to the cyber-security practitioner or a lawyer who knows about international law. 4) To make matters worse, there are different national definitions as well, so the People’s Republic of China means something entirely different with the term than the UK or France or Germany.

Technical Definitions

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines active cyber defense as ”Synchronized, real-time capability to discover, detect, analyze, and mitigate threats and vulnerabilities.” This is as technical as it gets. NIST’s focus is on synchronizing different cyber-security functions such as detection, analysis, and mitigation of threats, all of which requires active, coordinated work-streams, processes and human resources in an organization to facilitate this. This is somewhat in line with their famous cyber-security framework that describes the different functions organizations should have to increase their security. This includes the ability to identify companies’ assets, detect intrusions through logs and alert systems and a having a response capability, as well as recovery plans after a successful breach. To me, it sounds like — and this is my interpretation — that active defense should be the norm, i.e., active defense is equal to good cybersecurity postures. As such, it is conceptually not that different. It does not entail novel functions compared to standard or non-active cybersecurity. The only differentiator in NIST’s definition might be the real-time synchronicity, as it requires the active coordination of all parts of cyber-security posture.

In contrast, the EU counterpart Agency for Cybersecurity ENISA describes active defense as something on top of traditional cybersecurity:

Active Defense is defined as a collection of intelligence capabilities that operate in an adaptive and monitored environment. These capabilities are deployed with the purpose of gaining knowledge about an adversary’s operations: e.g. motive, tools, and sophistication. An example of a realistic Active Defense deployment can be the utilization of an isolated environment, configured and enriched with information that would closely resemble a real one, and with the capability to track all movements of an attacker with high verbosity.

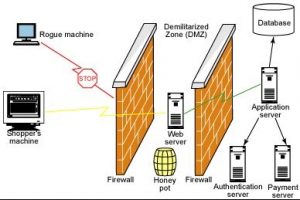

For ENISA, the additional element that differentiates traditional cybersecurity from active defense is the added intelligence component. The example given is the traditional “honeypot”, which means setting up an isolated subnet or demilitarized zone exposed to the Internet, which attracts adversaries. The idea of a honeypot is that attackers leverage their offensive tools and tactics against this seemingly high-value target, where the defender already waits to monitor all the steps taken by the attacker. Honeypot servers allow logging and studying the behavior of adversaries, and thus can provide useful intelligence for the defender.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303341315_Novel_Methodology_for_SCADA_Security/figures?lo=1

Arguably, most companies don’t necessarily need such honeypots, but it can be a useful addition to the cybersecurity program in more mature or high-risk organizations that actually can use the data that is gathered from monitoring attackers behavior. This implies that analysts enrich the data gained from monitoring adversaries and use it to fix vulnerabilities in one’s defensive posture. But this requires additional efforts by organizations: they require additional infrastructure as well as monitoring and analyst teams to enrich and make sense of the behavioral data. If that data is not used to bolster defenses, then it is rather worthless to have honeypots and an “active defense” posture under ENISA’s understanding of the term.

The notion of deception through honeypots is also present in other definitions. The security company Fortinet writes on its blog:

“Active defense is the use of offensive tactics to outsmart or slow down a hacker and make cyberattacks more difficult to carry out. An active cyber defense approach helps organizations prevent attackers from advancing through their business networks. […] Active defense involves deception technology that detects attackers as early as possible in the attack cycle. Active cyber techniques include digital baiting and device decoys that obfuscate the attack surface and trick attackers.”

Notice that for Fortinet, active cyber defense is part of offensive tactics that are normally directed against adversaries. The other definitions by NIST and ENISA don’t include offensive measures in their definitions of active cyber-defense.

The line of demarcation between passive and active defense

ENISA argues that offensive countermeasures “aim to source all required intelligence about an adversary’s operations, e.g. motive, tools, and sophistication, through the compromise of an adversary’s environment.” Although the definition of cyber offense is another can of worms, for the matter of simplicity, it is often understood as attacking and breaching foreign systems beyond your perimeter or your jurisdiction. Given this definition of cyber offense, for ENISA, active defense means something entirely different compared to offensive countermeasures. There are some similarities, of course, such as the goal to gather intelligence about the adversary, its tools, behavior and motives, but the point of demarcation is the network perimeter: active cyber defense for ENISA ends at your firewall and your perimeter and as soon as another network is breached, we are talking about offensive measures.

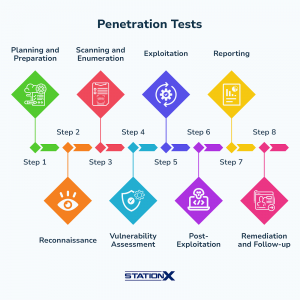

This exact line of demarcation also is frequently made in the offensive practice of penetration testing, which describes the security practice of attacking one’s own network to identify weaknesses in one’s security posture and strategy. Pentesting involves the use of offensive measures with the intention to utilize this knowledge to fix found vulnerabilities. For legal and ethical reasons, pentests rely on a clear line of demarcation between purely passive and active practices: For example, passive reconnaissance means gathering intelligence about the target via public sources, but without engaging its defenses. Looking through LinkedIn, scouting employees on social media, checking public DNS registries, analyzing the Darknet for previous data breaches for passwords and email patterns etc. don’t require a pentester to engage with the network defenses of the target. In contrast, passive reconnaissance becomes active as soon as an interaction with the adversary system takes place. Active reconnaissance includes network scans and active enumeration that send manipulated packets to the target’s IP address and public facing systems to see what services respond and what ports are open. This includes “banner grabbing”, i.e. sending requests to servers and analyze their response message to identify the version of services running on these servers. This also includes “vulnerability scanning” of IPs to detect weaknesses in the configuration of public-facing systems at the edge of the network perimeter. In sum: passive turns active the moment that data packets are being sent towards a target server. Notice that at this stage, the network defenses are only being probed, but not overcome. Sending data packets to a server is not necessarily malign, as it is a normal function of most network protocols: your web-browser sends similar requests to websites it wants to access and if you try to log in to an FTP or database server, your applications send similar requests.

So we have noticed that there are degrees of activeness: passive scanning does not interact with target defenses, but active scanning does. A step further would be utilizing the knowledge gained from these active scans to assess vulnerabilities for further exploitation. This would be steps 4 and 5 in a typical pentesting process, as outlined in the image:

https://www.stationx.net/penetration-testing-steps

This indicates that we can conceive degrees of activeness on a spectrum.

The spectrum between passive cyber-defense and active cyber-defense

So far, we talked only about the technical and tactical level of IT-Security, such as pentesting individual systems. But the same notion of active and passive can be found on the strategic level that defines goals and ambitions of entire countries. For example, take note of France. In its grand strategic document, “The Strategic Review of 2018”, it is written:

“To complement existing cybersecurity measures, new, more active and aggressive techniques are beginning to be implemented more and more systematically. Between a purely passive defense and resolutely offensive measures, they are grouped in the category of active defense measures. So-called “honeypot” techniques aim to lure attackers to dummy targets so that they reveal their tools, making them easier to spot. This technique, widely used by researchers, enables them to observe a wide range of malware.”

From this, we can gather that active defense measures sit somewhere on a spectrum between “passive defense” and “offensive measures”. It might also include aggressive measures, which likely means penetrating networks. Again, the honeypot is mentioned, which appears to be the common-sense technique of active defense so far. But there are others.

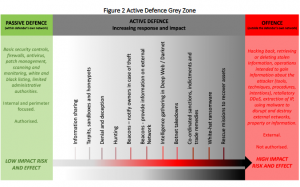

The US active cyber defense alliance lists numerous other techniques of active defense besides deception, such as the hunting for threats within one’s network, the use of beacons files that trigger alerts when they are touched by an adversary in one’s network as well as Open-Source Intelligence gathering on the dark net. One interesting element is that this idea also includes techniques on different levels: i.e., most of the techniques such as honeypots or beacons lie within the responsibility of individual organizations, whereas coordinated interstate sanctions and trade remedies, as well as botnet takedowns are being decided at the state or strategic level. So we have a vertical distribution of active defense measures as well as a horizontal one, as the techniques sit on a spectrum between defense and offense. This horizontal spectrum describes where the activity takes place: the defenders’ network, outside the defenders’ network, or inside the adversaries’ network. The vertical spectrum describes who is in charge of conducting these measures: organizations or state entities such as law enforcement agencies.

Note that in this spectrum, the line of demarcation between offense and defense is not entirely clear. Earlier I argued that we can utilize the line of demarcation made by pentesters: offensive measures begin at the stage of active reconnaissance of adversary systems (i.e. sending data packets to them). If we take this as a starting point to analyze the practices listed by the US active cyber defense alliance, we can deduce that practices of “botnet takedowns”, “white hat ransomware” and “data rescue missions” might require active scanning. The last two certainly involve probing adversary systems plus exploiting vulnerabilities in them to take over control of these systems. While botnets can be dismantled in various ways, such as by physical seizures of command and control systems, it often requires sending data packets to the bots to disable the malware. This would cross our demarcation line, but it depends on the individual botnet type. Some other of these practices do not necessarily require sending data packets to target systems, such as information gathering, sandboxes, deception, beacons, Darknet OSINT.

What we can learn from this is, active cyber defense might involve offense, but it must not necessarily include it. My esteemed colleague Sven Herpig also makes the point that cyber offense can be part of active defense, but it must not necessarily be part of it.

The location of active defense measures: gray, blue, red

From the US active cyber defense alliance, we can gather three more insights: 1) the spectrum introduces the notion of risk, impact and effect, meaning that offensive cyber is high-risk and induces damaging effects, whereas passive security does not. We will talk about effects in a later blog post. 2) the location where activity takes place matters, and 3) the actor in charge matters (states or law enforcement vs. individual organizations). We will come back to actors as well, but let’s talk about location for a minute. Active cyber defense measures and practices take place somewhere and are directed against systems that have a physical location.

In that sense, passive defense is often to be said to be confined to one’s own network, often called the blue space. When taking a company as the reference points, this means its entire IT-infrastructure, for which it has legal responsibility. For entire countries, this normally means any IT-system hosted on its sovereign territory. Of course, the borderless nature of the internet makes this perimeter definition somewhat fuzzy. The wider internet is often described as the gray space. It is not really controlled by anyone. The best example is the Darknet, which is not owned by any single entity. Similarly, peer to peer file sharing networks or messaging protocols are geographically highly distributed and this not easily locatable in any one jurisdiction. Some practices of active defense also take place in this gray area: for example, for setting up honeypots, gathering open-source intelligence (OSINT) and passive reconnaissance. The red space typically means IT-infrastructure controlled by adversaries. This notion corresponds with the line of demarcation we discussed earlier.

While this seems intuitive, the problem with the location or perimeter-based understanding of active cyber defense is the current reality of networking. The traditional network perimeter has been losing relevance with the advent of the cloud, infrastructure-as-a-service, software-defined networking, web-applications and mobile computing in the 2010s. There is no longer a clear perimeter line in most organizations that shields the inside (the domain) from the outside (the Internet and cloud services). This diffusion and distribution of infrastructure applies both to the defender and the attacker: attacks nowadays use virtualized cloud instances, hijacked servers as jump-off points, botnets and more that are diffused over the internet and not sitting in one target location that can be attacked. So in many cases, the attacker does not have a clear-cut red space as well.

Preemptive vs. preventive active defense measures

Having discussed the location, another line of delineation and lens to understand the term active defense can be the timing of the activity. Indeed, many observers argue that active cyber defense is temporally located before an attack takes place. For example, this idea is developed in a German op-ed by my esteemed colleagues at Fraunhofer Institute SIT:

“Passive cyber defense measures are those that are taken preventively without a specific cyber attack being foreseeable. Meanwhile, active cyber defense measures are those that are taken reactively if a specific cyber attack is imminent and foreseeable or has already begun.” (my translation)

They argue that passive cybersecurity is primarily about prevention, namely about preventing attacks from occurring in the first place. For example, preventative security controls are those that prevent incidents from occurring by blocking certain activity. This includes security hardening, disabling default accounts, firewalls blocking foreign traffic into a network, intrusion prevention systems that block malicious packets, but it also includes things like physical barriers and locks that prevent unauthorized, physical access to servers.

For the authors from SIT, active cyber defense is being initiated once a more specific cyber-attack becomes visible. The terminus technicus here is preemption. Many readers might remember the notion of preemptive strikes, which was invented during the Iraq war of 2003 to justify the US invasion to preempt the imminent threat of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (which weren’t there in the first place). In military parlance, preemptive means you strike first to gain a military advantage before the enemy attacks. Now we’re leaving pure technical cyber-security lingo and are entering the territory of different epistemic communities such as the military and international law. A preemptive attack takes place before the adversary attacks to prevent this very attack. Both prevention and preemption try to address a future threat, but in preemption, the threat is said to be clear and directly unfolding, whereas prevention is more long-term oriented. You beef up your cyber-security to prevent against the more abstract notion of a potential future breach, but you don’t have any intelligence that a breach is imminent. The threat is less immediate, there is less direct evidence of it materializing.

The trouble with the preemptive logic is the potential for abuse, as was the case with the Iraq invasion. Back in the day, the US put forward a controversial legal argument for “preventive self-defense” against the alleged threat of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction. This stretched the traditional understanding of self-defense under international law, which typically requires an imminent threat. Of course, what imminent means is not obvious in many instances. Many legal scholars argued that preventive war against non-imminent threats is not permitted under the UN Charter.

To preempt, one requires a lot of visibility of adversary actions to see the imminent attack unfolding. The trouble is, we often don’t have the required visibility to detect the signal in the noise. To make matters worse, things might be clearer on the conventional battlefield than on the digital one: in the physical space, you can see enemy troop movements and increases in tank and artillery stockpiles via satellites and drones. Armies require huge logistics components, trucks, tanks, artillery, tents, crates with ammunition and food for thousands of people that have to be moved to the border or the region where one intends to attack. A US carrier strike group certainly gets noticed when it navigates in international waters. Physical geography makes stealth attacks harder to conduct. So, in principle, it is possible to know that an adversary might attack soon, but it is much harder to pinpoint where exactly (the exact direction of the advance) and the precise timing (in a day, in a week?). We have seen such difficulties in the ramp-up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which happened over the course of a year.

In the cyber domain it gets even trickier because here you don’t have large, observable troop contingents that are bound by geography such as mountains and rivers. In the cyber domain, one cannot necessarily see the amassing of adversary troops, and it is less clear when, where and how an attack might manifest. Of course, if one has an “active” (here we go!) threat intelligence component that actively looks for manifestations of threats, such as chatter on the Darknet or visible probing and enumeration attempts at your network firewall or your DMZ, one might see the preparatory or reconnaissance phase of a cyberattack. The reconnaissance phase is the first phase in complex, offensive cyberoperations that is being followed by other steps.

Complex, offensive cyber operations are often described in terms of a kill-chain, which is a series of steps the attacker must follow. It has a lot of conceptual similarity with the pentesting process described earlier. In a nutshell: first, an attacker must first identify target systems, second scan them and enumerate vulnerabilities. Then, in the second step a malware can be written and tailored to the specific target system and its unique vulnerabilities. Third, the malware must be transported to the target, often via phishing emails or sometimes via USB drops. Fourth, typically unwitting users must click an active the malware, to trigger the code that exploits the system and creates initial access for the attacker. Fourth, initial access is often temporary and can be lost, for example if the exploited system reboots. For that purpose, the attacker must gain persistence in a fourth step called installation. This can imply the creation of a backdoor or the creation of a new user with remote login credentials. The sixth step is privilege escalation. In many attacks, the first victims tend to be low-privilege users that have limited access to network resources. Therefore, attackers attempt to compromise further user accounts until they gain administrator level access to a network. When this is achieved, the attacker has command and control capability of a network and can carry on with the actions on the objective, such as triggering destructive effects, stealing data or maintaining a silent presence.

https://www.deepwatch.com/education-center/what-is-a-kill-chain-in-cybersecurity/

The problem is, that these kill-chain steps have different degrees of visibility. For example, for cyber defenders it is difficult to separate problematic reconnaissance attempts from normal “internet noise”: I.e., what is normal, automated probing and rattling on your door knobs, versus what are concrete breach attempts? On my website, I get thousands of automated probing and login attempts per day, but this does not tell whether this is a targeted attack or just normal “noise” of having a web-service running on the internet.

Same with phishing, which is normally phase three of the cyber kill chain: What is ordinary reconnaissance phishing (to see if a domain is active), what is automated credential harvesting, and what is targeted and tailored (such as spear phishing)? And even if you can make the distinction, you don’t know how imminent an attack is and what type of attack is coming your way: in other words, in cyber we often don’t know the imminence nor the nature of the threat until we see its effects on our networks (i.e., data being exfiltrated, encrypted or machines being wiped), we don’t know whether an effect occurs at all and if it can be detected (which also often is an issue). Within the cyber-killchain, cyber defenders might detect an attack either during the delivery stage, when suspicious emails are identified and deleted, or during the exploitation stage, when the running of a script, installation of a malware or backdoor is being detected by Intrusion Deteciton Systems or Endpoint Protection and Response/Antimalware solutions on the hosts. This, of course, requires that detection mechanisms are indeed in place and technically able to detect signatures of the attack (which is not the case, if the attack is novel or utilizes unknown 0-day vulnerabilities or happens via an attack vector, where no sensors are installed).

So I am not really convinced that the visibility required for preemptive action is really there, at least not in all cases. It might be in some cases, but often it is not. But what we can say is that in the cyber-domain, the pre-warning time available to detect the concrete materialization of an effect (i.e. a payload being executed, malware being downloaded, registries being manipulated etc.) is much shorter than on the conventional battlefield. Oftentimes, the hardly visible reconnaissance phase takes weeks to months of preparation, whereas the actual unfolding of the exploitation phase (from gaining initial access to privilege escalation, lateral movement and gaining persistence), is often measured in hours. In 2024, it has been reported that the average time between initial access on a network to the installation of the malware shrunk down to mere hours. For less sophisticated cyber-criminals the time between initial access and installation might be a day or two. This is an extremely short time window for defenders to detect malicious activity, especially if it starts on a Friday or during holidays.

Takeaway message

Let’s take stock for now: For technical agencies, active cyber defense is an addition to traditional cyber-security, in the form of better synchronization of security functions or a deceptive capacity (honeypots) to generate additional intelligence on attackers. Active cyber defense might entail offense (i.e. engaging with the network of an adversary), but it does not necessarily need to. It can be conceived as a spectrum between defense and offense. The line of demarcation between passive defense and active defense is the moment where data packets are sent to the victim. Active cyber defense has a geography: it can happen within the network perimeter of the defender, but it might involve other “spaces” such as the gray space of the internet or the red space, the perimeter of the attacker. The latter involves a higher risk and the materialization of concrete effects on the target. Active cyber defense also might have a temporal logic: Its goal might be to preempt an imminent attack from occurring, rather than to prevent more abstract, future threats. These are the different axes of activity.

So far, so good. What also became apparent is that active defense seems to entail “more” than passive defense: it employs additional tools and measures like honeypots and deceptive techniques with the aim to gather intelligence on adversary behavior. What remains to be discussed in the next blog posts is what it actually entails to be “doing” active cyber defense, what tools can be used and what different types of reactions or “countermeasures” can be part of active cyber defense.