How to defend against disinformation and information warfare is one of the key questions that democratic states face within the current environment of geopolitical tension and worldwide authoritarianism. Typically, awareness campaigns and fact-checking have been heralded as solutions to this growing problem. However, if artificial intelligence, deep fakes, and synthetic media increase in quality and the distinction between fake and reality gets ever murkier as these solutions face diminishing returns, other solutions are needed.

To engage with this problem field, we conducted a wargame with the help of IFSH Peace and Security Master students in the context of the horizontal “Doing Peace” research project during summer 2025. Wargames are an interactive format to practically simulate conflict and crisis and to scope out potential solutions and have been used in military and business continuity and crisis planning for years. Their relevance as an experimental research method in areas with limited data access and black box scenarios has been rising as well (Greenberg 2021).

Wargaming Scenario

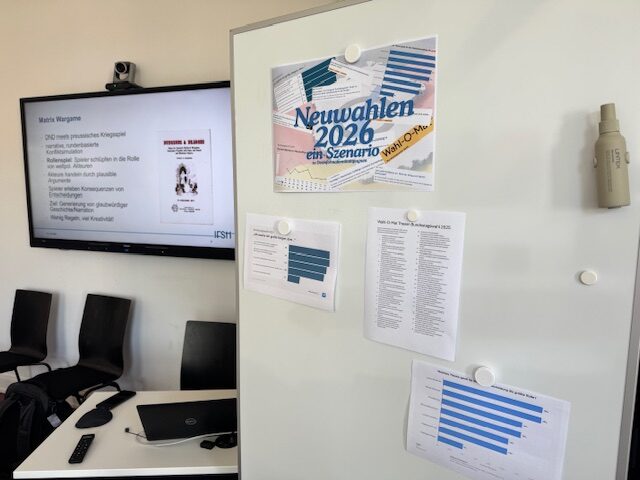

We confronted our students with a semi-fictitious scenario of a coalition crisis within the German government and a sudden election in the summer of 2026. The geopolitical context was roughly that of 2025, with the war in Ukraine ongoing, economic decline in Germany, unreliable transatlantic partnerships, and growing relevance of artificial intelligence (AI).

Within this scenario, students roleplayed four key actors who tried to profit from this scenario and achieve their predesigned agendas: 1) the federal government trying to maintain the integrity of the election, 2) a foreign intelligence agency attempting to undermine this election with disinformation, cyberattacks, sabotage, 3) a social media company with a large market share in Germany attempting to maximize profits governed by a techno-libertarian Euro-skeptic billionaire, and 4) a right-wing opposition party attempting to reach a majority in the election. Each actor had individual objectives, hidden agendas, maxims for action as well as support material (for example, a playbook on how to conduct disinformation campaigns).

We opted for a narrative-driven and turn-based MATRIX wargame methodology where actors act through arguments that are discussed collectively for their plausibility. Players propose plausible and implementable actions for their actors and present them turn by turn. Success and failure of actions were also facilitated through dice rolls. The aim of this method is that players have to deeply identify with the agency they represent and think through the lens of that actor and then actually make decisions based on incomplete information. The beauty of wargaming is that this aspect matches reality. Other players then react to the decisions made by others before, and thus a chain of consequences unfolds that players have to live with.

Figure 1 Scenario Material and Briefing

Findings: Democratic challenges in defending against influence campaigns

In total, we conducted two 4-6-hour gaming sessions. During our sessions we discovered the following reoccurring topics. First, it is hard for a democratically elected government to fend off subversion attempts that try to exploit responsibility grey zones within government bureaucracies while following due process and the rule of law. Hostile actors specifically target democratic legal loopholes. It is difficult to defend democracy if defenders have to obey the rules, while hostile agents and opposition parties can bend and break existing rules with little repercussions.

Second, it is hard for democratic governments to seize initiative. In our playthroughs, the election campaigns were mostly driven by the foreign intelligence agency and the right-wing opposition party, whereas the government was mostly just reacting. The government was hardly able to seize the initiative and surprise hostile influence agents. In both playthroughs, the governments were rather defensive and passive, while the foreign intelligence agencies were active and forced the government to react. Coming ahead of the curve is thus a central challenge for democracies.

Third, we discovered that typical government initiatives and defensive strategies such as awareness campaigns, fact-checking initiatives, enhancing cybersecurity, or election integrity monitoring were hardly effective against high-speed, targeted actions by hostile intelligence agencies, often amplified by social media. Most of the government actions were, by nature and the need for interagency coordination, rather slow and inflexible, and their effects played out later in time. The same holds true for government communication. Proactive strategic communication to raise awareness, educate, and debunk foreign influence campaigns as quickly as possible is crucial. However, interagency bureaucratic processes are often too slow, stakeholders are too risk- averse to communicate effectively with the population through modern streams of communication. Press conferences are simply not enough in the current information environment.

Fourth, we discovered that governments need to reassert their position over corporations that have enormous amounts of power over the media environment. In our wargaming scenario, the social media company actively engaged in polarization and trolling, but the government had few tools to control this international company. Given the current, international environment, the idea of private-public partnerships might have to be revalued if some corporations clearly have the ambition to work against civil democratic societies and their governments.

Last, recurrent feedback from the participants was that the wargame closely matched the reality we are living in. As such, it is a valuable tool for political entities to practice and train.

Figure 2 Gameplan

Research findings: Does awareness through wargaming help in spotting real vs. synthetic disinformation campaigns?

Beyond our ambition to raise awareness of the workings of disinformation campaigns, our second, more scientific goal was to test whether awareness is helpful in detecting influence operations. In other words, we wanted to test the assumption that better education and awareness of the workings of disinformation and foreign influence campaigns result in participants spotting and critically reflecting on such campaigns.

For this purpose, we designed a quasi-experimental setup. We employed a within-subjects pre–post design to assess participants’ ability to detect synthetic versus real disinformation campaigns. On the first day, we briefed our players about the methods, strategies, and examples of previous disinformation campaigns. We designed a simple online survey to test whether the wargame exercise enhanced the capability of our students to detect disinformation campaigns. We held two surveys, one before the initial briefing and the first game session and one at the very end, after players played two rounds of the game.

The surveys consisted of four descriptions of disinformation campaigns, so eight in total. Four of these campaigns were historical, i.e. they happened in the past and thus were real. Four of these disinformation campaigns were synthetic and artificially generated with the help of Perplexity AI.

Examples of Survey Items

- Synthetic: A KGB disinformation campaign during the Vietnam War to divide the anti-war movement in the US through leaks.

- Real: A Chinese influence campaign against the 2024 election in Taiwan to stir sentiment against the US and the Taiwanese government.

- Real: An influence campaign by GDR intelligence to subvert West German Bundeswehr generals arguing against NATO missile rearmament during the 1970s and 1980s.

- Synthetic: Influence campaign against the French election of 2024 to support right wing parties.

The descriptions of these campaigns and the prompts to generate them were structurally homogenized and similar across all cases, with the only variation being the historical setting and the geographical location of the campaigns.

During the surveys, the participants were presented with four disinformation items and asked to judge for each whether it was real or fabricated. For every item, an accuracy score was computed by comparing the participant’s judgment to the ground-truth authenticity label (1 = correct classification, 0 = incorrect classification).

For each participant and survey wave, an individual detection rate was calculated as the mean of the four item-level accuracy scores, yielding a value between 0 and 1 that represents the proportion of correctly classified campaigns. Detection rates were also computed post-intervention using the same scoring procedure and then averaged across all participants to obtain overall pre- and post-intervention detection rates.

Our hypothesis was that students who learned about the workings of disinformation campaigns, a) through the briefing and b) through actually playing a disinformation scenario and conducting their own influence campaign would likely have a better ability to determine fake from real disinformation campaigns.

We found that the average detection rate before the wargaming session was 0.58, while the detection rate after the second wargaming session went down to 0.21. In essence, the wargaming treatment had a negative effect on detection. In other words, awareness campaigns and fact-checking are not enough to counteract the effects of sophisticated influence campaigns fueled by the power of large language models. Distinguishing between reality and synthetic creations becomes ever harder.

But these findings remain limited in generalizability. Our sample size was rather small (n=6). Future research has to test with more robust checks and larger sample sizes whether this finding holds.

Outlook

Conducting wargaming exercises in university and teaching contexts proved to be a beneficial and entertaining praxis. Wargaming methodologies closely align with the ambitions of the “Doing Peace” project, since wargaming is a praxis that needs to be done and exercised. It is an essential method of integrating research, knowledge transfer, and engagement and a suitable tool to raise awareness. Warming also is quintessential participatory praxis, and student engagement was high. However, given the prevalence of disinformation campaigns and their increase in quality and reach, through the help of large language models, individual awareness-raising is simply not enough and does not scale well to the societal level. Therefore, political interventions are required to limit the spread and reach of such campaigns through social media platforms.

Against the backdrop of mounting geopolitical challenges—including increasingly assertive authoritarian powers—an additional question is whether liberal democracies may no longer be able to avoid considering a greater reliance on offensive cyber operations and strategic communication tools within frameworks of both cyber and information deterrence, and how such approaches should be balanced against the associated risks.

By Matthias Schulze, Tobias Fella and Lina Grob (Deep Cuts project).